It’s been a checkered run that’s delivered former World Tour surfer Dustin Barca from Kauaiian street fighter to politics. More checkered than any politician you’re likely to find. The difference is he doesn’t hide from it. Nor is he ashamed of it. Jed Smith follows the Kauaiian hardman, turned World Tour surfer, turned MMA star, turned environmental crusader and would-be mayor, on his latest fight.

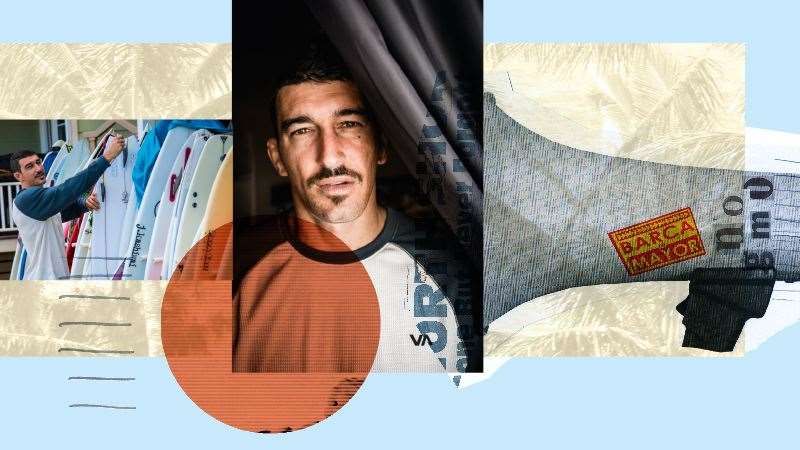

Sitting opposite me in a pair of khaki pants with no shirt on, he has a presence alright. The presence of a warrior; calm bordering on deadened, persuasive yet without even having to say a word. If it’s how he looks in times of peace, I ponder, you’d hate to see him mad. Dustin Barca does not have the face of a politician. If he showed up to kiss your baby you’d probably call the cops. With his infamous gap-toothed grin – lost after his fin hit him in the mouth (“Not a fight,” he laughs) – most haoles (mainlanders) will tell you they’re downright scared of him. That’s not something he’s proud of. But you get the sense he is aware of it.

Dustin Barca has lived a life of conflict. He’s been in one fight or another for as long as he can remember; fights over waves in the heavily localised and often violent arenas of Kauai and Pipeline; fights for respect from his brutal Polynesian mentors; and fights for survival in the Mixed Martial Arts ring. He’s as good at conflict as anyone you’ll find though with age and a young family behind him now, he’s better at picking his fights. And he’s picked a real humdinger lately.

“It’s the modern day overthrow,” he tells me of the Genetically Modified Organism corporations (GMOs) that have taken root in the islands. “They’re poisoning my island, my kids’ island.” Barca recently launched a crusade against the Hawaiian government and the GMO manufacturers he believes have corrupted it, culminating in a bid for the seat of Mayor on his home island of Kauai.

Raised on the breadline by a single mother who worked three jobs just to put a roof over he and his brother’s head, Barca’s early life was one of hardship. There wasn’t always enough money for food. Instead they’d dumpster dive, collect discarded food from their friends who worked at the shopping centre and grow their own organic crops in the backyard. On the days he ditched school to surf – which were many – Barca would hang out by the mall and eat left over plate lunches. “Andy (Irons) use to always tell me I had the biggest chip on my shoulder,” he recalls of childhood friend and the late three-time world champion, Irons. “And I did. Not having much growing up and wanting it all – I think (the chip) was my way of motivating myself to get it,” he says.

With his stomach filled he’d head to Hanalei Bay, one of the most violent and localised waves in the world, also where a surfing movement was underway that would become one of the most significant in surfing history.

“Everyone who made it out of Kauai came from there. We had the most competitive people in the world in one place. Fifteen kids that were just trying to better each other, just on a mission to make it,” he says. Andy Irons, Bruce Irons, Jesse Merle Jones, Reef McIntosh, Kala Alexander, Kamalei Alexander, Kai Garcia, Braden Dias, Jesse Merle Jones, Keala Keneally, Danny Fuller, Aamion Goodwin, Sebastian Zietz, just to name a few. All from one unexceptional little beach. Barca remembers fights almost every day, usually between outsiders and the local Polynesians trying to keep the place secret.

“They’d always tell us, ‘It’s for you guys, to keep it sacred for the next generation.’ And I took it to heart 150%,” says Barca. Though he also admits he overdid it. His teenage years became little more than surfing and fighting at points. He also had a mouth on him, and that was something his elders wouldn’t tolerate. “I was a cocky kid so I caught my fair share of lickings. I was the whipping boy of the (feared surf gang) Wolfpak,” he says. They come no more fearsome than the Wolfpak in surfing. Born on Kauai, they arrived on the North Shore of Oahu in the late 90s and today hold the keys to the most prized real estate in surfing, Pipeline. Hated, feared and adored in equal measure, it’s their way or the Kam Highway at Pipe. With many believing it’s a necessary evil in a world as unregulated as surfing. Where a single moment of carelessness at a wave like Pipeline can commit another man to injury or death. But the Wolfpak might never have become what it was if it wasn’t for a fight Barca himself had as a wiry 17-year-old.

The North Shore had been simmering for a while already. The presence of the feared Da Hui crew had melted away under a glut of travelling surfers and complicated dealings with the surf industry. Pipe was fast becoming a circus. People were dropping in, lives were being put at risk, the local law was not being followed. That was about to change. Barca had just been kicked out of the NSSA American Nationals surfing contest for cheating on his exams. The kids he’d been staying with ratted him out. He was gutted. It was meant to be his ticket to the big leagues but instead ended with his main financial backer, Rip Curl, tearing up his contract. Heartbroken and angry, he flew straight back to Kauai and took up a series of low paid manual labour jobs – landscaping, construction, painting – and seethed.

“All the time I’m just thinking fuck the industry, fuck everybody. I’m just gonna go to the North Shore and surf,” he recalls. The winter rolls around and he shacks up at Braden Dias’ house – the infamous Hawaiian enforcer, Wolfpak kingpin and “The Guy” at Pipeline back then. Half a dozen of Kauai’s best surfers – and enforcers – are in the same house – Kala Alexander, Chava Greenlee, Kai Garcia, Andy and Bruce Irons. All from Kauai, all in the one house, all scrapping to make it. Dias is supporting them all; providing three meals a day plus beers for his whole crew. Barca, aged 17, arrives in a rage. “I was at a point in my life where I was trying to prove myself, I was a young punk and I wanted to be the man,” he says. He runs into his former Rip Curl boss at a Triple Crown party at Haleiwa Joe’s, the local nightspot. They almost brawl. Current ASP commentator, Strider Wasilewski breaks it up. He talks some sense into Barca but he’s not around in the morning. It’s on for real.

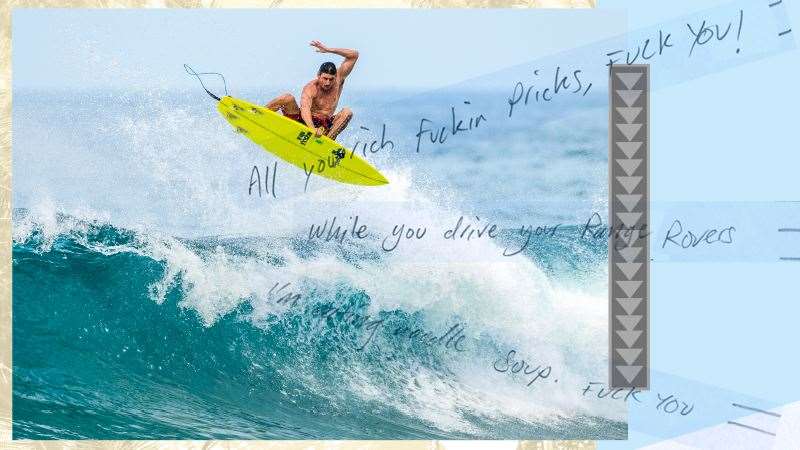

“Pop-pop-pop, I tune him up good,” recalls Barca, showing me the flurry of punches that did the damage. News travels quick. Soon Barca has an audience of Rip Curl bosses on Dias’ front porch. They’re demanding an apology from Barca as well a reprimand for their former charger. The Hawaiians are in no mood. “We have the who’s who from his company on the porch, all the bosses, everything. I told them all, ‘All you rich fucken pricks, fuck you. While you’re driving your Range Rovers I’m eating noodle soup. Fuck you’,” he says. From then on everything changed on the North Shore.

“That was the beginning of the Wolfpak overthrow. Right there a lot of people, anyone who dropped in, it got super heavy from that point on. That’s how the regulating started. It was always going on somewhat but that kicked it to the next level.”

Fighting and surfing have a strangely intertwined history, especially in Hawaii. The most infamous chapter was of course the Busting Down the Door saga, in the winter of 1975, when Aussie surfers, Rabbit Bartholomew, Peter Townend and Ian Cairns were harassed, beaten and threatened with death over a series of statements made in the surf media. Statements which expressed their desire to dominate Hawaii’s waves and demonstrate their supremacy over local surfers. To native Hawaiians it was seen as another attempt by foreign forces to take away their culture. Since the overthrow of Queen Lili’uokalani by American revolutionaries in 1893, native Hawaiians have fought a losing battle for autonomy. Surfing, a sport which was first performed by ancient Hawaiian royalty and later exported around the world by Duke Kahanamoku, is seen as one of the strongest preserves of traditional Hawaiian culture. Any slight against it is taken seriously.

“Our queen was overthrown, hundreds of thousands of Hawaiians died when the white man came here from all the diseases they brought, and people come here and wonder why Hawaiians are so hard to understand or this or that? It’s because we’ve been fucken exploited for years and one of the few things we have left are our waves. And you’re not gonna come and take our fucken waves, too. You took our land, you took our fucking monarchy,” explains senior Wolfpak figure, and Kauai pro surfer, Kala ‘Captain’ Alexander.

As the years passed more and more foreign surfers made their home in Hawaii. Including Brazilians, some of whom were masters of the traditional Brazilian fighting style, jiujitsu. One such master made his home on Kauai, opening a gym and teaching a number of local surfers the fight style. Among them was North Shore enforcer and former Kauaiian pro surfer, Kai Garcia, who would go on to win the World Championship of Jiujitsu in Brazil. Another jiujitsu and Mixed Martial Arts expert from Hawaii is BJ Penn, regarded as pound for pound one of the greatest fighters in the history of the sport. Garcia and Penn turned MMA into something of a national past time in Hawaii, particularly within the alpha-male dominated surfing community where it became the weapon of choice for settling disputes at Pipeline.

Barca was among the keenest enthusiasts, merging his proficient kickboxing and street fighting skills with Brazilian jiujitsu to become a world-class talent. He hoped to one day emulate his fighting heroes, Garcia and Penn, and make it to the Ultimate Fighting Championship. But surfing came first. His Kauai boys, Andy and Bruce Irons, were dominating the World Tour and Barca wanted on.

“They were like my big bros. I just wanted to be like them, be as good as them,” he says. By the time he’d qualified for the tour, however, Andy and Bruce had already quit. Bruce was never really wired that way while there was little left for Andy to prove – he’d beaten the greatest of all-time, Kelly Slater. Beaten him again and again on his way to three world titles and a place among the sport’s all time greats. Alone, homesick and struggling for motivation, his debut year on tour was a disaster. A string of poor results were capped by a sensational boilover with then Brazilian world number five, Adriano De Souza, resulting in a physical altercation.

“I got so burned out that year. I didn’t feel like anyone was my friend. I was an alien on that tour,” he says. While travelling through the European leg Barca was given some literature pertaining to the activities of GMO corporations in Hawaii. ”I just started diving into it, looking at the science from both sides and finding common sense in the middle and just being like, wow, this is fucked up,” he recalls.

Following his debut year on tour, Barca was relegated from the World Tour. He wasn’t bothered much. He was jack of competing, anyway. Plus it gave him an excuse to focus on his other passions: surfing Pipe, cracking heads in the MMA ring and taking on the world’s biggest food corporations. First the fighting career. There was no doubting Barca’s aptitude for brawling. His early years at Hanalei Bay ensured that. A lifetime spent surfing the heaviest waves of the planet, meanwhile, had honed his reflexes and anticipation to a superhuman level. The lip at Pipeline moves much quicker, and with more force, than any human. His rise was meteoric. His first major outing came in the all belts, all weights Absolute Division of the Kauaiian jiujitsu league. He beat five men in an hour to win the event outright. He was still celebrating a few days later when he turned out at a friend’s wedding and ran into Andy Irons, his childhood friend, with whom he’d fallen out with recently and not spoken to in six months. When Andy saw Barca, all beaming in his fighting belt, the tension melted away instantly. “He was like, fuck brah, you gotta fight (professionally). It’ll be nuts,” he recalls. A few days later Andy was dead. Killed by a heart attack and a cocktail of prescription drugs and illicit substances alone in a hotel room in Dallas, Texas.

This was a different kind of madness to any Barca had felt before. He began to question what more he could have done. Guilt set in. Then Andy appeared to him in a dream. “He told me basically, ‘Brah, get over it, there’s nothing you can do about what happened’. After that I was kinda just, I’m gonna fucken fight, I’m gonna fucken do it, I’m gonna live my dreams, I’m gonna do everything I wanted to do,” he says. But the heartache wasn’t over. While preparing for his first professional fight another of Barca’s close friends, Kauaiian big wave surfer, Sion Milosky, passed away. This time in a big wave accident at the Californian big wave spot, Mavericks. ”I was just like, ho…” says Barca. “It just fuelled my fire to fight. Now I was representing my island, my friends and family and my friends who weren’t with us anymore,” he says. His first opponent already had nine fights – a terrible mismatch on paper. In the ring his opponent didn’t stand a chance. “I choked him in under a minute,” says Barca.

A pro surfer from a tropical paradise with Barca’s backstory was a tantalising prospect for promoters. His second fight was scheduled on one of the biggest undercards in Hawaiian MMA history – the Arlovski vs Lopez card at the Blaisdell arena, also featuring BJ Penn’s brother, Reagan. His opponent owned every amateur MMA and kickboxing belt in Hawaii. It went longer than a minute but it was the same result.

“I beat the shit out of the guy,” says Barca. His patented flying knee and jab-fake-elbow did the damage, earning him a TKO after the second. It ranked among the biggest upsets in Hawaiian MMA history. “My name just went pew!” he says. His third fight was a demolition. A young kid from Oahu’s west side. Barca slammed him 15 times before knocking him out on his feet. The kid was tough. That’s how they breed ’em on the west side. He went the distance but he was sore by the end of it.

By his fourth fight, Barca was already calling the shots. He scheduled his dream fight: a bout on the North Shore in the middle of the Triple Crown. He arrived on Oahu that winter beaming. “I was too happy,” he says now. On his first day of preparation he combined all his loves into one, opening with a surf, followed by a striking session and rounding the day out with some jiujitsu. It was too much. A fatigued Barca blew out his knee in the wrestling session, tearing his MCL and icing any chance of the fight. Injuries are part of the MMA game. Barca knew that. But not being able to surf for an entire winter, that was a cruel kind of torture. He needed something to take his mind off it. He began immersing himself in a new fight: the fight to rid the islands of GMOs.

The island of Kauai evokes a prehistoric kind of beauty. Its craggy cliffs, luscious greenery and abundant natural resources is what drew Steven Spielberg here to film the big budget classic, Jurassic Park. Barca grew up in Kilauea, the island’s organic farming capital, where he was surrounded by fresh produce and the farmers who swore by it. Today, the island is famous for its grass-fed cows and organic foods, except that most of it is exported for big profit to the mainland leaving the island to import 90% of its food. More concerning for Barca, however, is the presence of GMOs in Hawaii and the large scale spraying of pesticides throughout his island and the rest of Hawaii. Some of the pesticides, like Aquazine, have been banned by large sections of the international community, including the European Union, forcing the chemical giants to double-down on their testing in Kauai.

Barca claims school children near one of the testing fields have been poisoned, large-scale die-offs of sea urchins have been reported and hunters have told him of finding pigs with giant tumours. On a larger scale, he’s also aiming to rid the islands altogether of GMO testing – a practice he believes is not only putting the future of farming on his island at risk but the human race in general.

“They’re splicing the genes with the chemicals they make, into the genes of the plants. Bugs will eat it and they will die instantly and they will be weed resistant, but after two years what they don’t tell people is that it creates super weeds. So now they have to make even heavier chemical resistant crops,” he says. Not to mention the potential consequences of consuming food that’s been genetically engineered to kill organic creatures.

“What a biotoxin does is it kills a bug. When a bug eats a plant and the biotoxic gene, they pretty much implode and poop their whole stomach out and die right there. Basically, we’re giant bugs,” he says. The science is still inconclusive. Three of four Hawaiian counties have attempted to pass laws regulating pesticides, GMOs, or both. Despite an attempted veto by Mayor Carvalho Jr, in 2013 Kauai passed a law requiring large farms to establish a 500 foot buffer around their operations and disclose the pesticides they were using; a move brought on in no small part by Barca’s grass roots activism campaign, which brought together a who’s who of the international surfing community, including Kelly Slater, with local residents and farmers.

A year later, however, it was overturned by the State in what was but one of several agriculture and food bills shot down by local, state and federal governments in the last few years. It wasn’t until Barca chanced upon a rally for the Mayoral incumbent and former professional football player, Bernardo Carvalho Jr, to find a number of GMO industry figures in the crowd, that he finally cracked. “All you corrupt fuckers! This shit’s over! I’m running for mayor already!” he was heard to yell before storming out.

The fight was on. With no financial backing, no campaign experience and no real idea of what being a politician entails, Barca was unquestionably facing an uphill battle. Though as he puts it, “I’m scared for my kids’ future and when I get scared, I don’t run away, brah. I face my fears.” But he did run. And paddle. And swim. All the way around the island of Kauai. In scenes reminiscent of Forest Gump, Barca’s main campaign weapon was simply to pound the pavement, drumming up local support as he ran a loop of the island. After paddling off the coast of a Kauai in a traditional three-man canoe, he swam to shore and began his remarkable journey – running 16 miles the first day, 28 the next, 26 the day after and 17 to round it out, conducting “listen-ins” with community leaders as he went.

By the end of it he claims to have “shaka’d every car on the island.” An experience he calls the “most enlightening” of his life”. “It was just conversations with god for four days straight … it brought me closer to the people, brought me closer to myself, brought me closer to god, and it brought me closer to the island,” he says. It also brought him closer to another remarkable upset. By the end of his campaign he was polling at 31 percent of the vote, earning him second place in the primaries and a shot at his nemesis, the GMO-backed Bernard Carvalho Jr, for the seat of mayor. It was more than most could have hoped for. But it wasn’t enough for Barca.

“I’m always disappointed. I always like to strive for perfection. I’m in no celebration whatsoever. I’m just learning from our mistakes,” he’d said after the results.

By the time I meet Barca another day is setting on Pipeline and the race for Mayor has long been lost. His grass roots campaign was no match for the millions of dollars in political donations his opponent had to draw on. In the end he fell 27% short of the vote required, totalling 8195 to Carvalho’s 14,688.

He emerges down the concrete steps of the Oakley House, onto the sand he first set foot on as a 12-year-old with fellow Kauaiian pro, Danny Fuller, the pair sleeping rough, eating out of bins and doing whatever they had to do to be near their Hawaiian surfing heroes back then. Today Barca waves to Fuller from the balcony of his top floor penthouse suite overlooking Pipeline. Fuller lives in the corresponding room next door. While Kauaiian pro surfer Reef Mcintosh occupies the same room in the Quiksilver House after that and surfing and jiujitsu legend Kai Garcia in the same room in the Volcom House beyond that.

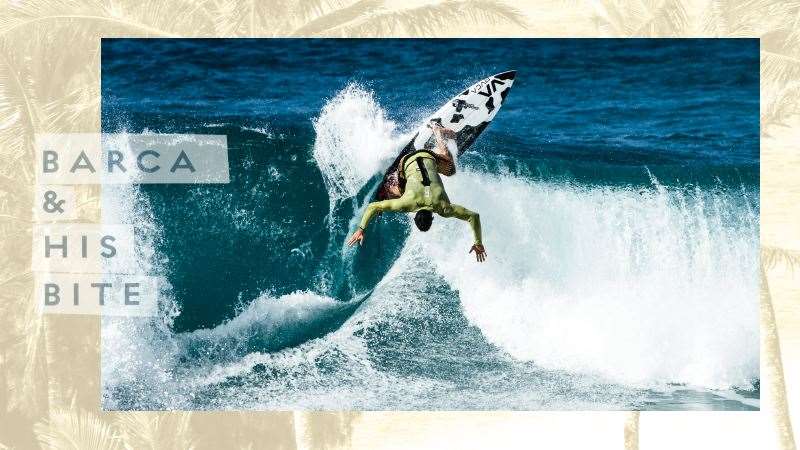

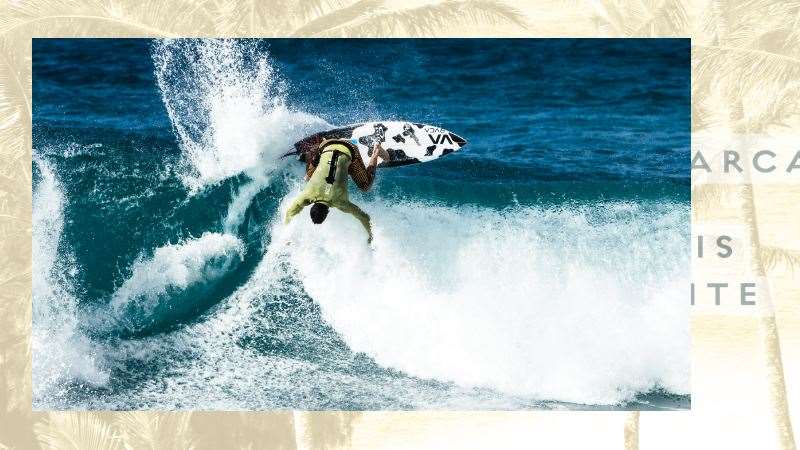

Barca’s wetsuit is scribbled in dirty hand drawn graffiti with the name of his sponsor RVCA. As he makes his way to the water, wolf whistles and howls ring out across the sand. The Wolfpak boys still own the North Shore and he lifts one arm in acknowledgment, letting his hand sag in a gesture reminiscent of their totem animal. Barca’s not proud of his past, but he’s not ashamed of it either. It just is, and now he’s moved on to a new fight, a righteous fight in his eyes. He might be a little rough around the edges but when there’s this much on the line, who else would you want in your corner “With the political thing, I’m always gonna be here,” he tells me. “I’m gonna be a thorn in these guys’ asshole till the day they fucken start doing some shit for this island … I’m ready to die for the future of my island.”

This article first appeared in the March issue of Tracks

Follow Jed Smith on Twitter https://twitter.com/@jed_j_smith