Spaniard Adur Letamendia perched precariously ‘twixt land and sea, perhaps matphoric for the Faroe Island, an ancient windswept Scandinavian archipelago halfway between Iceland and Norway. So old and weather-beaten as to forever resist change. Its daily winds resonant with isolation.

Spaniard Adur Letamendia perched precariously ‘twixt land and sea, perhaps matphoric for the Faroe Island, an ancient windswept Scandinavian archipelago halfway between Iceland and Norway. So old and weather-beaten as to forever resist change. Its daily winds resonant with isolation.Gunnar, the serene blond manager of my Tórshavn hostel, leaned back in his squeaky desk chair and watched the morning rain pelt his office’s double-paned window.

“Here you get all seasons in one hour,” he said quietly. The wind shrieked. Black clouds arched over the town. Twenty minutes prior there was a snow flurry; forty minutes prior there was blue sky. Tórshavn, population 19,000, is the largest city in the Faroe Islands and yet it is Europe’s smallest capital. Gunnar loves his hometown.

“The air is warming up now,” he said. “Should be a fine day.”

“I was thinking of taking a drive,” I said.

“Better to wait for the rain to stop. Here, let’s have some coffee.” He led me to the hostel’s small, cluttered kitchen, and with pride he showed me his new high-tech, stainless steel, French-made espresso machine.

“This is the future of espresso. I am going to sell these machines. The people here, they will thank me!”

I hadn’t had caffeine in nine months, but something about the Faroese rain condoned it, so I sank a few cups of espresso while chatting with Gunnar.

“The tourist season, it is changing now,” he said. “There was an article in National Geographic. Already my bookings are up, and it is only April. Usually tourists don’t come until July or August.”

He was referring to the November/December 2007 issue of National Geographic Traveler, which ranked the Faroes at number one out of 111 islands in the magazine’s “report card for the world’s islands,” saying this: “Remote and cool, and thus safe from overcrowding, the autonomous archipelago…earns high marks from panelists for preservation of nature, historic architecture, and local pride…Lovely unspoiled islands—a delight to the traveler.”

If there was any harbinger for a boost in Faroese tourism, that was it. “Millions of people in the world saw that article,” Gunnar said ruefully, “and many of them are wanting to visit a new place.”

“But you run a hostel. Isn’t that what you want? Steady business?”

“Yes, but not so it is overwhelming.”

“Why will people want to come here instead of going to Iceland or Sweden?”

“Because we are more isolated, of course. People think we live in caves, but you come here and see that it’s a modern society. Culturally it’s probably more original, if you can say that. We have preserved a lot of the old rituals that disappeared with Christianity coming to the other countries. We have the old chain-formation dance and the grindadrap, our traditional whale-killing ritual; the national sport is rowing with traditional boats that look like Viking boats. We have all those things. We are different and smaller than Iceland and Sweden.”

“More quaint,” I said.

“Yes. But maybe tourism is the only way many Faroese people will realize that they aren’t living in a—what do you call it—in a bubble. They think their village has the perfect society. They’re very hostile toward foreigners— not hostile, really, but they think that everything else outside of their village is crap, you know?”

“But you Faroese are preservation-minded, right? I would think that alone would prohibit excessive tourism and keep things low-key here.” “That’s the idea,” Gunnar said.

For 60 years the Faroes, like Greenland, have been an autonomous appendage of Denmark, though the Faroese shun the European Union and the Danish language and general bustle of Copenhagen, 1,200 miles away.

“Denmark is Denmark—we are Faroese,” a large chain-smoking man named Fridtjof in a Klaksvík pub told me. He was white-bearded and looked like a weather-beaten Santa Claus. “We speak our own language, we have our own parliament and our own flag. The Danes can never take these things from us.” He pulled his wallet from a coat pocket and slammed some Faroese currency on the bar. “Look, we even have our own money!”

“What if Denmark stopped subsidizing you?”

“This is not possible. Denmark needs us. It is the same as Greenland. Did Greenland vote for independence? No. Did we? No. Everybody knows that a little country like this needs help. All we can export are wool and fish.”

“Perhaps you could export this beer, too.” I was on my fifth bottle of Klaksvík-brewed Green Islands Stout. “It’s quite good, and it’s getting me buzzed.”

“Beer is from the Vikings, you know, so people drink a lot more here,” Fridtjof said. “For example, they drink twice as much in Denmark as they do in other countries. It’s like a world record. You can drink a lot of alcohol without having a problem.”

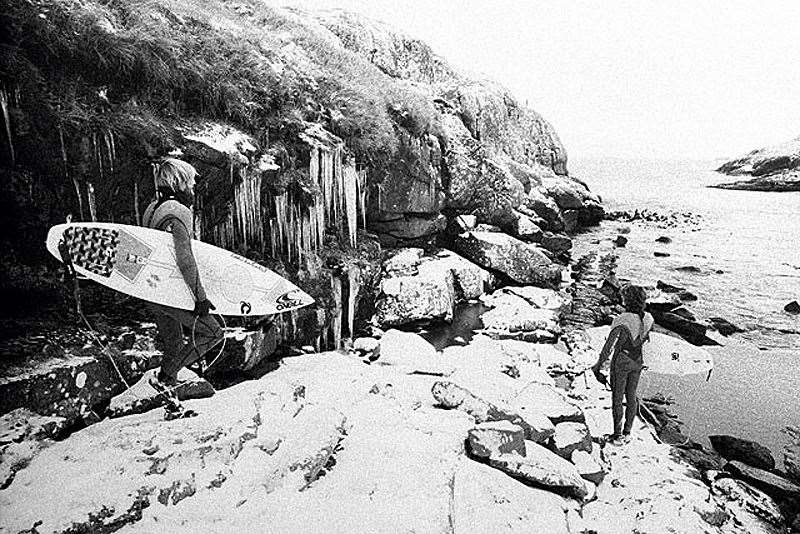

The following afternoon I emptied several bottles of a different kind of local beer (Föroya Bjór Pilsnar) with David, a tall, thin, pale man in his late 20s who had recently become the first native Faroese surfer. A visit from some American and French pro surfers in 2007 inspired him to start surfing, and we’d met randomly this sunny spring day on a grassy coastal bluff on Sandoy, the relatively flat “island of sand” which had the country’s best surf potential. The swell was up and the wind was right, but the waves were funky at best, ruined by jagged bathymetry and hideous rock mazes. I was shooting landscape photos and David was looking for something to ride on his dark blue SurfTech 7’3” egg that he’d bought in Norway for the equivalent of AU$1,460 (“I think I got ripped off.”). David was highly educated and friendly and spoke loudly with a deep, powerful voice, extolling extensive knowledge about his beloved Faroes, even if it wasn’t endowed with Raglans and Jeffreys Bays or even a classic beachbreak.

“Those Americans, they surfed up there,” he said, pointing north to a crude A-frame peak blasting into an exposed shelf of boulders and seaweed. “They said it was okay.”

Born in Tórshavn, David lived in Denmark for one year as a child before returning to Tórshavn until he was 16. He attended high school in Denmark, then at age 18 he traveled around Scandinavia looking for a job in precision mechanics. He found one in southern Denmark, did research and development there but eventually grew weary of it, so again he returned to Tórshavn and, with his parents, started the first Faroese aquarium.

“We are a fishery nation, so we figured we should at least have an aquarium,” he said. “That was the argument for getting the funding.” “How about some artificial reefs for surfing?” I asked. “Ha! That will never happen. The Faroese are familiar with only two things associated with the sea: you are either fishing in it, or you are dying in it.”

Speaking of death-by-sea, I questioned David about the infamous Faroese ritual, the grindadrap, something that has come under international fire in recent years and is certainly unfavorable with animal rights activists and sealife-loving folks like surfers. Anyway, was grindadrap indeed cruel and evil?

“I can definitely understand peoples’ reactions when they see the bloody pictures,” he said, “just like with surf pictures where you never see what happens before or after the picture is taken.” “What’s the process?” I asked.

“Basically, a guy in a fishing boat stumbles upon a pod of whales. Then he calls the police, usually, and then they contact these guys who are appointed to be the head guys to organize the killings. Everybody who wants to participate goes down to the harbor, takes their boat, and sails out to the whales. On the boats, you bring a lot of people because then you get more shares of the whales. Depending on the wind or the daytime or the sea current or the tide, then you decide where to go with the grind. This can take hours and hours and hours. You just leave the whales there. You don’t push them or anything. You just keep an eye on them. And then slowly you form a line of boats and you make a wall. Whales naturally will move away from these boats, so you slowly drive the boats toward a beach—like herding sheep, you see. If the tide is right, you start pushing the whales by accelerating the boats, so they’ll start swimming faster, and when you’re close to shore, the whales have gained so much speed that they create a wake behind them. So they end up just floating up onto the beach—they beach themselves. And then all these guys are standing on the beach, waiting with a hook attached to a big rope, so they hook each whale and pull it up onto the beach. But instead of a normal hook, we use a hook that you put into the blowhole, and you pull it by the blowhole. The whale doesn’t feel any pain. One guy has a big knife and he’ll cut the whales’ throats. You can kill 200 whales in 20 minutes. It’s really fast. There are hundreds of people on the beach with their knives. It’s very organized.”

Somewhere under the Faroese rainbow lies a special place, a rarefied, wave from the Norwegian Sea. Photo: Michale Kew

Somewhere under the Faroese rainbow lies a special place, a rarefied, wave from the Norwegian Sea. Photo: Michale KewLast November there was a posting on Surfersvillage.com called Pilot Whale Slaughters in Faroe Islands Raise Protests featuring gruesome photos of the whales being killed at Faroese beaches, the sea blood-red, with pasty men raising knives to the shiny black cetaceans.

“While it may seem incredible,” the posting read, “even today this custom continues in the Faroe Islands (Denmark). A country supposedly ‘civilized’ and an EU country at that. It is absolutely atrocious…This protest message…calls on Denmark, of which the Faroe Islands is a part, to stop the slaughter and urges recipients to pass on the message in order to raise awareness of the issue.”

As the Faroes were not a surf destination, the appearance of a grindadrap protest piece on a surfing website confused me, but I agreed with British scribe Alex Wade, who, two days later, wrote his own online story called “The Faroe Isles Surf Trip Is Off.”

“Perhaps the Faroese should be allowed to carry on with (grindadrap), for, as they argue, it’s been a part of their culture for centuries?” Wade wrote. “Perhaps, too, hardline Somali Muslims should be allowed to stone women to death, for this, too, has long been a part of their culture? Likewise, shouldn’t we repeal the ban on fox hunting, because, for centuries, this was an embedded part of the fabric of English country life?”

But on that windswept Sandoy beach, David refused foreign fury.

“That Canadian guy from Sea Shepherd, Paul Watson, he used very aggressive tactics to expose grindadrap. He can’t see it from our point of view. He should be sailing his vessel into slaughterhouses where the chickens and cows are. They’re having terrible lives, and then they’re slaughtered. Our whales are having a great life until they are slaughtered. It’s 100 percent ecological.”“What’s the cultural significance of it?” I asked.

“It’s a huge part of our diet. Some say that 25 percent of protein consumption in the Faroes comes from those whales, but it varies, also. You get some years without a single whale, and you get some years with a lot of whales.”

Wildlife advocates and potential surf tourists like Wade might be pleased to know that recently, perhaps in a move to quell naysayers and stop the grindadrap altogether, the Danish government declared the whales to be unfit for human consumption, citing their high levels of mercury.

Which unfortunately did nothing to improve the surf of the Faroes, a green, treeless archipelago of rocky, waterfall-laced isles far removed from the 21st century that penetrates the rest of Scandinavia. Poised in the stormy ocean between Scotland, Norway, and Iceland—a trinity of cold North Atlantic surf havens—the Faroes are rife with swell but bereft of surf spots. The coastline is mostly steep and inaccessible and the surfable beaches are few, typically located on the islands’ southern and eastern coasts, which are sheltered from prevailing west swells. East swells are rare and usually plagued with onshore wind. Sheepshit-scented offshores are anomalous but do occur.

Yet to me none of this meant anything but a shade of inconvenience. Where there was swell, there was surfing.

The road was smooth and perfectly maintained, tracing the edges of scenic fjords where fishermen in boats worked lines and sailed out for the day’s work. I passed villages—most identical with small grass-roofed homes—where laundry flapped in the breeze, chickens and geese scurried, young girls rode horses; sheep were all over the road in many places and I wondered if there was a statistic somewhere saying how many sheep were hit by cars each year in the Faroes.

Bore through hillsides were several tunnels, essential for such a small, mountainous country. The new tunnels were wide and bright and highly economical; the older tunnels were low and narrow and drippy and very dark, some of them dating back to the 1960s. Without the tunnels, the route would be painfully long and slow and precipitous and from Tórshavn it would take hours to reach Oyrarbakki and its Shell station, which played Beethoven at the pumps. While I filled up, an attractive young blonde in the car behind me noticed the surfboard in my van. “What is that?” she asked.

“A surfboard.”

She rolled her eyes. “Oh, dear. What is wrong with you?”

“I’m a surfer.”

Sheep shit and piss covered the roads in the villages, which seemed deserted. I saw very few people—either they were in Tórshavn working, or they were holed up inside, or they were simply gone. Occasionally I saw a person walking along the road, exercising in the freshest of sea air. In the town of Eiði was a beach with strong potential—reefs galore. It appeared to receive large swell, because there were boulders and logs washed over into the adjacent lagoon, and the road’s pavement had been ripped off, also pushed into the lagoon. Loitering on the beach were shaggy sheep with their ears tagged, all spraypainted for identification: green foreheads, pink butts.

In Elduvík I waved at a boy riding a go-cart; he glowered back at me. Sheep baaahhed as I drove past, the road ending at a pretty bay ribbed with swell; unfortunately the bay was too deep for it to break, except to rise up and crash straight onto the rocky beach. Tiny Elduvík, population 102, would never host a Faroese surf spot, which goes for 95 percent of the 693 miles of Faroese coastline.