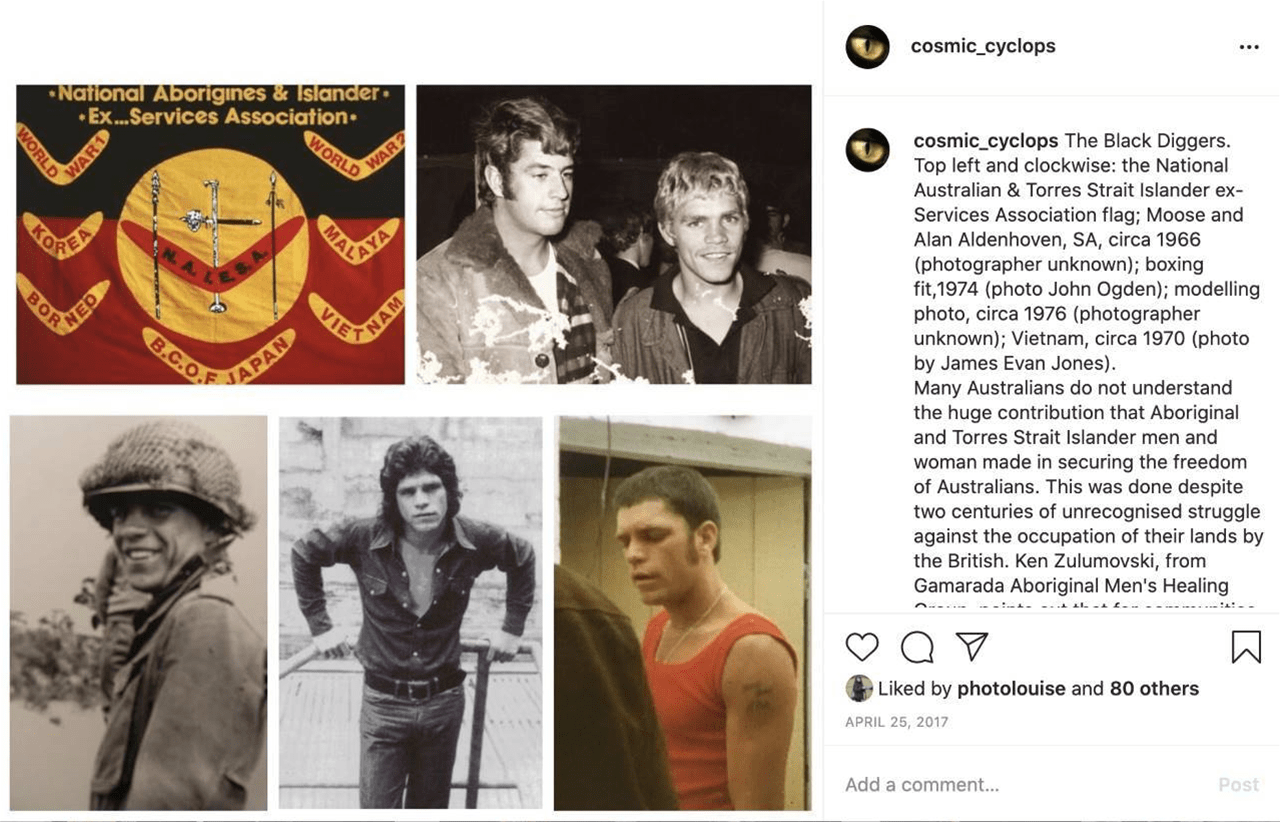

First Nation people had been enjoying the surf for thousands of years before the Europeans invaded and stole their lands. It happened here, as it happened in the spiritual home of surfing, Hawaii. In Australian waters, the coastal clans were largely a canoe culture and were known to take their craft out well beyond the breakers. Perhaps the first Aboriginal surfer of the modern era was Allan Aldenhoven. He started to get stoked in surfing in 1964, the year Midget won the World championship, and around the same time, I got my first fibreglass board. Allan was about 4 years older than me, and I looked up to him as one of the older crew. Everyone knew him. Handsome and funny, he was part of the wave of rebellious youth that got into surfing on the back of Hollywood’s infatuation with the burgeoning Californian surf scene.

One of the most successful surf films from this era was The Endless Summer, first shown in 1964, presenting a vision of white surfers “discovering” the perfect wave at Cape St. Francis in Apartheid-era South Africa. Few know that California had its own form of Apartheid, with Jim Crow-era laws segregating Black swimmers from wealthy whites. At Santa Monica, “Inkwell Beach” — as it was known at the time — was a roped-off, 200-foot zone designated for the black community. It was here that Nicolás Rolando Gabaldón (1927-1951) taught himself to surf, before being encouraged to surf at Rincon and other beaches along the Californian coast. He is credited with being California’s first documented surfer of African American

descent, and instrumental in breaking down racial barriers in the 1940s.

During the mid to late sixties, Al Aldenhoven was one of the most recognisable faces of the South Australian surf scene. With his black skin and peroxided blond hair, he was soon given the nick-name ‘Boonga’, in that shit-stirring tradition where surf crew usually bestowed the most offensive handle that they could come up with. Allan took his nick-name with good humour, but if anyone used this derogatory term with malicious intent they would feel the sting of his lightning-fast fists. Most people didn’t even know he was Aboriginal, and Allan didn’t give it much thought. He was only 4-years-old when his “mixed-race” mother suddenly died. Dorothy Aldenhoven had been part of the stolen generation and never knew her Aboriginal family. She too was 4-years-old when she last saw her mother – after being taken by the police from her Manangoora home in the Top End, and placed in a Methodist Mission on Croker Island in the Arafura Sea, as part of the government’s policy to assimilate mixed-race kids.

Allan was born in the old Darwin hospital on Anzac Day 1948, a date that marked the landing of Anzac troops on a small stretch of beach on the Gallipoli Peninsula, an event considered to be the nation’s baptism by fire. Allan’s red-headed father, “Meggsie”, took his four sons to South Australia after his wife died. Named after his uncle, an Australian Rules football sporting hero, Allan was sent to live with his namesake on his farming property at Butler Tanks on lower Eyre Peninsula, not far from Elliston, the site of a notorious massacre of 250 Wirangu people, forced off a coastal cliff to their deaths in 1849. Out here, amongst these vast fields of wheat and barley, Al was raised tough and wild. Taught how to hunt and box by his ‘Unk’, he had good athletic skills, before a bout of encephalitis knocked him flat for a few years.

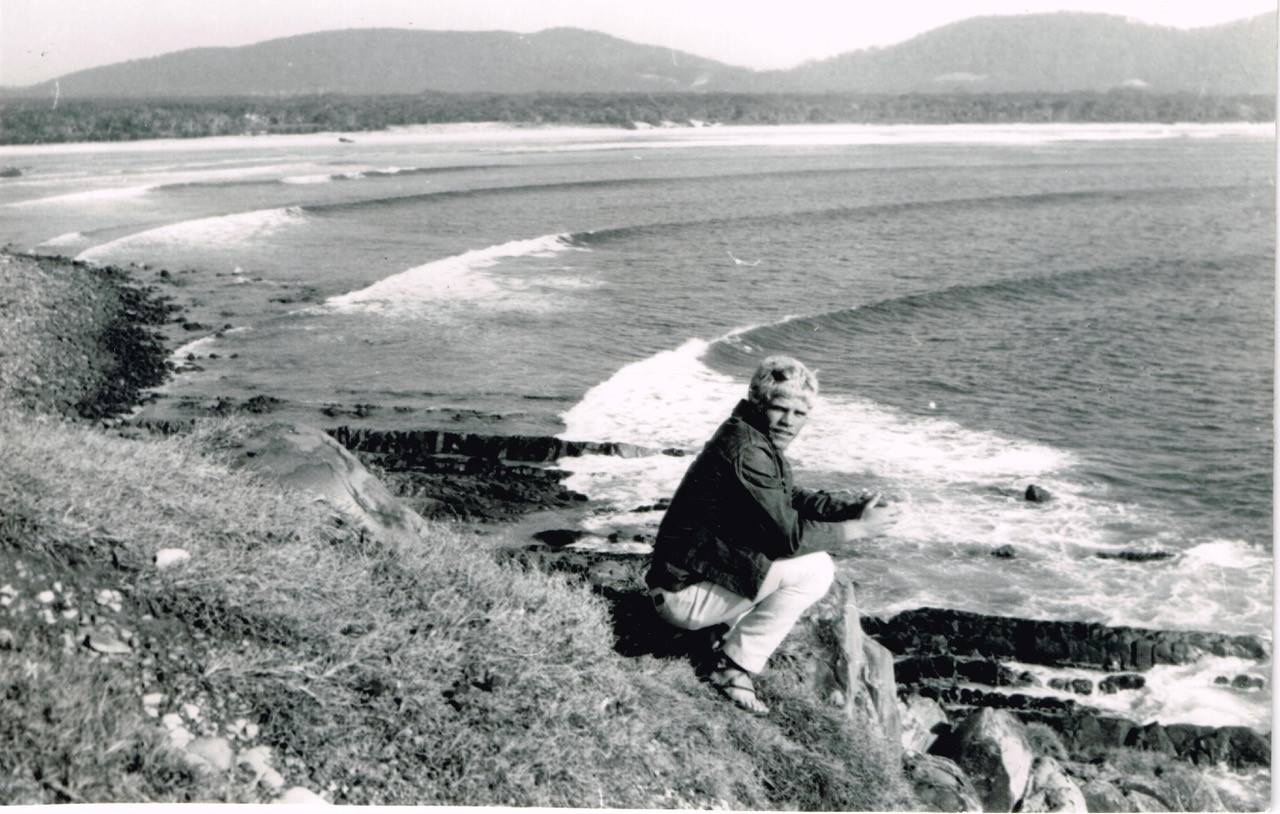

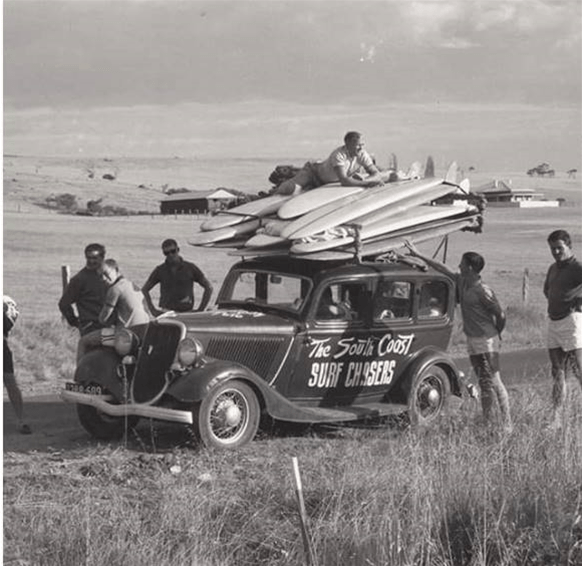

On finding surfing, Al was competent but not a standout. However, by the maxim of “the best surfer is the one having the most fun”, he was a champion. He was always there, hooting and yelling when one of his mates got a good ride and went on many surf adventures to the South Australian desert breaks or up the east coast, scoring good waves at Crescent Head, Angourie and Kirra in 1967. I remember him coming into JA’s surf shop in Adelaide when I worked there as a grom sweeping out the shaping bays in the summer of 1968-69. His broad smile and sense of fun was infectious.

Those few years of fun in the sun would be interrupted by the Vietnam War. Al was called-up in 1968 – just a year after Aboriginal people had been recognised in the constitution – and by the following year was serving as an Infantry Section Leader, leading his men on search and destroy missions in the Vietnamese jungle. Having survived the war, like all Vietnam veterans in the later years of the war, he returned home to a hostile reception and scant recognition for his service. He was one of the older crew who told me about what was really going on in this Coca-Cola war, and by the time my marble was pulled out of the barrel (Numbered marbles representing birthdates were chosen randomly from a barrel to determine who was conscripted), I was a full-blown conscientious objector. Although Al was older than me and drafted earlier, we had both been 19 when our draft papers came in - too young to legally vote or drink at the time, but old enough to kill. After that, our experiences were very different.

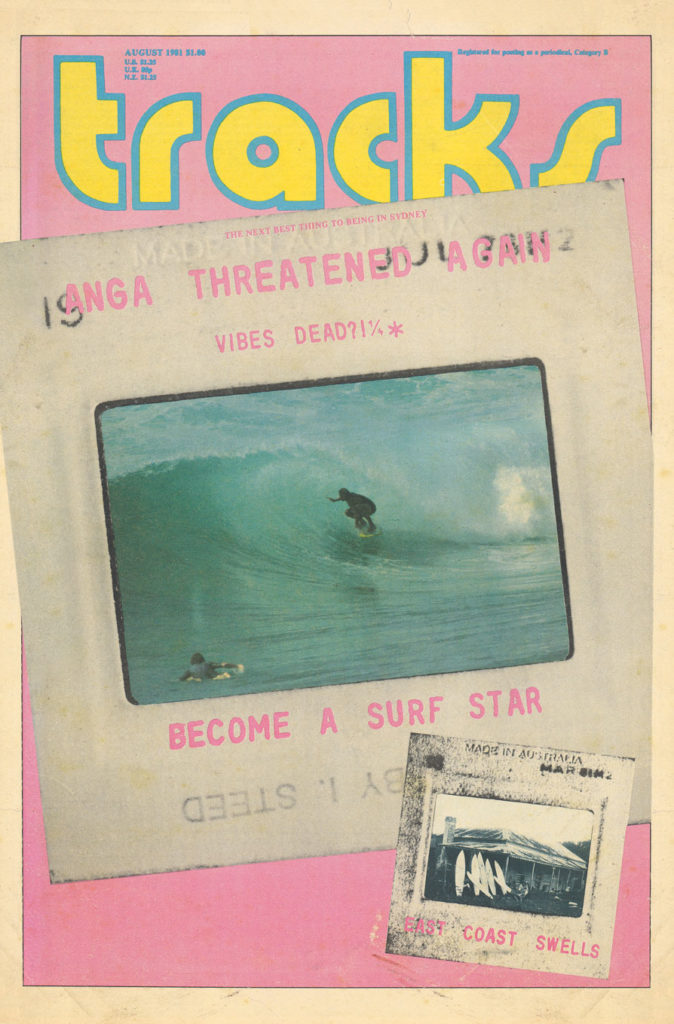

Despite later being crowned the Australian Welterweight boxing champion after being discharged from the army, Al was changed by his experiences in Vietnam. He never really escaped his demons and died in February 1979 under highly suspicious circumstances. I was living in WA and working for Tracks magazine when I got the news that he had been found dead in his cell at the Port Adelaide police station, hung by his own belt. The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (1987–1991) did not review his case as it fell outside the terms of reference for the inquiry, which was limited to such deaths between 1 January 1980 and 31 May 1989.

Al was a fighter … and he would always be there to protect his mates if there was trouble. Like Otis Carey and other contemporary Indigenous surfers, he didn’t take crap from anybody. Many of Al’s mates believe that he was murdered by corrupt cops for being an “uppity black”. In recent years I have wondered if his nick-name did niggle at him, and wish I could sit down with him now and talk about his extraordinary life. #blacklivesmatter

FOOTNOTE: John Ogden was the WA correspondent for Tracks in the late 1970s. Over the last two decades, he has written several books on Indigenous Australians, and is about to release a book, tentatively titled WHITEWASH, about an African Australian life-saver at the Freshwater SLSC when Duke Kahanamoku visited in the summer of 1914-15. Ogden is currently working on a longer-form story of the life of Allan Aldenhoven. Announcements on release dates will be made on his Instagram page: #cosmic_cyclops